When an email was sent to Long Beach State students in the Department of Film and Electronic Arts about an opportunity to sit in a discussion with four distinguished female directors via Zoom, it was a reminder that both faculty and students are examining how to better support women in the industry.

And those lessons start in the classrooms.

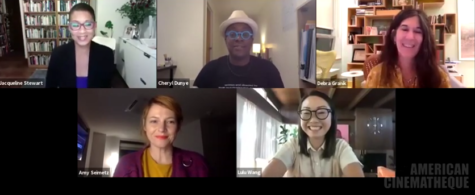

Sarah Len, film and electronic arts community engagement specialist, sent the email in September about the conference Women Make Film, featuring directors Amy Seimetz, Lulu Wang, Cheryl Dunye and Debra Granik. There, the directors deconstructed inclusivity for female students in cinema and cinema itself.

During their schooling, the panel of filmmakers said that they were surprised by the amount of riveting films by women and women of color that existed.

“There was stuff out there,” Dunye said. “You had to find it.”

Fourth-year English literature major and film minor Noelle Awaida said film professors at CSULB are doing an adequate job, but there aren’t enough lessons dedicated to more overlooked filmmakers, including women and women of color. The most inclusive film class Awaida had sat in was Film and Culture.

“Women and BI-POC are sometimes a topic we move on from quickly in classes,” Awaida said. “When classes reference popular filmmakers, whether that be through a historical context or current mainstream creators, they’re mostly white men. Of course this does depend on the professor and I think some do recognize this issue.”

Awaida wants to work in screenwriting or script supervising, but dreams of working as a diversity consultant in cinema. She said that as a Middle Eastern and Latina woman, she understands the skewed perceptions of who can be a success, prompting her need to change the narratives within the media.

Katie McNamara, a fourth-year majoring in both string bass performance and film and electronic arts with a specialization in creative nonfiction film production, said some professors are more progressive than others. She finds that today’s nonfiction-oriented film professors are a reflection of the curriculum they were brought up with.

“The ‘Bonnie and Clyde’ [film] ending is amazing, sure,” McNamara said. “But the amount of times I’ve had to watch that one scene, I could be learning about so many different people who did astounding, groundbreaking things in the industry who aren’t male.”

The film history course, McNamara said, was the most diverse class she was in. But since moving onto major-specific classes, she credits documentary courses as more diverse in terms of perspective, directors and voices.

Helen Hood Scheer, assistant professor in the Department of Film and Electronic Arts, is an award-winning filmmaker behind documentaries like “JUMP!” and shorts like “The Apothecary.” Scheer is also one of the key figures behind the next generation of documentary filmmakers at CSULB.

“Helen is so proactive about us getting out there,” McNamara said. “She engages in discourse about what’s happening right now in documentary, what’s changing, what needs to be changing.”

Instead of attending regularly scheduled class, Scheer required McNamara’s class to attend a virtual convention called Getting Real ‘20 that focused on different jobs and identities in documentary filmmaking. McNamara said Scheer shares information about various events and screenings with her students often.

Scheer feels it is necessary to expose her students to skills from directing, recording sound, producing and more in order to build women and men up for an unforgiving industry.

“I make sure that I train all the students to wear every hat,” Scheer said.

Scheer’s insecurities with documentary filmmaking stem from being a perfectionist rather than a lack of role models in the documentary field.

“I think the problem is not so much the curriculum, the problem is what happens after our curriculum,” Scheer said. “The problem is the barriers to access in the professional world. In order to get jobs, you often need to know people and have past credit from other jobs. If you’re not getting hired, then it’s hard to grow and get promoted within the industry.”

Scheer added that the curriculum at CSULB can improve and it’s something that new hires and existing faculty are working towards.

Len is bringing the conversation of inclusivity to students and faculty through informative email forwards and publicity and works closely with the department chair and director, Anne D’Zmura, to keep the conversation alive.

“We really strive to listen to our students,” Len said. “Opening our ears to them because ultimately, that’s how we’re going to learn to be able to create a more inclusive environment and safe environment that’s productive to their learning.”

Anne D’Zmura was unavailable to comment.

Spring 2019 graduate and filmmaker Janine Anne Uyanga directed the short “Justice Delayed” in 2019, the story of a Black man’s short-lived relationship with his younger brother. The film tied for the Best Narrative award at the 2019 CSU Media Arts Festival.

“Really focusing on stories and the message you want to demonstrate is definitely something I lead with,” Uyanga said.

In solidarity with Scholar Strike last month, CSULB created an anti-racism resources page that includes Uyanga’s film. Uyanga believes that they’re a product of their self-determination instilled in them by CSULB’s creative nonfiction writing track.

Uyanga didn’t let the lack of their representation in the film curriculum skew their perception of success.

“I was cognizant of the lack of diversity within the teachings that we were learning,” Uyanga said. “I knew that learning these things was the foundation for me to at least take that knowledge and then I can be the one to change that.”

Corrections to this story have been made to better reflect the curriculum of the Film and Electronic Arts Department on Oct.5 at 12 p.m.