The uptick in violence against the Asian community in the United States does not exist in a vacuum.

Instead, violence against the community—and violence does not have to be physical to be deemed violence—is deeply intertwined in the history of the U.S. from government actions to harmful media perpetuations.

But the coronavirus pandemic created an opening for racism and prejudice to breed, evident in former President Donald Trump’s usage of calling the coronavirus the “China Virus,” a term perpetuated quickly via social media, according to a study published in the American Journal of Public Health in April. The results found that, when comparing hashtags #covid19 and #chinesevirus, anti-Asian hashtags increased in association with the #chinesevirus, highlighting just how dangerous this narrative is.

And according to Dr. Preeti Sharma, assistant professor of American Studies, this rhetoric has fueled a modern day “yellow peril,” a term used during the 1800s that targeted Asians. It claimed they were a threat to the West and would disrupt democracy, a fear mongering tactic to paint Asians as “other.”

But other instances of ignorant statements arose, as pointed out by Dr. Sharma.

Gov. Gavin Newsom made a false statement in June of last year, saying that the site of community spread of COVID-19 in California was a nail salon.

In the entertainment industry, members of the Asian community have been subjected to racist caricatures like Mr. I.Y. Yunioshi from “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” as well as the more recent, troublesome depiction of Bruce Lee in “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood.” Asian women in film are subjected to stereotypes and fetishization, portrayed as sex workers and are often shown as docile and subservient.

If it’s not a caricature or stereotype, then it’s the absence of seeing Asian actors in mainstream sitcoms or blockbuster films.

Or, it’s the long perpetuated model minority myth, that touts Asians—ignoring the challenges individual ethnic groups face in favor of perpetuating the community as a monolith—as being socioeconomically successful. It is used to perpetuate antiblackness and pit the Asian community against other marginalized communities.

There is violence that occurs every day.

Accents are mocked. People are made the punchline of jokes centered around tired stereotypes. And, as Dr. Kim calls it, there is the “lunchbox experience,” where Asian American children in school become aware of how their culture’s food differs from their schoolmates’ food. In the process, they are singled out, teased or made to feel ashamed and different.

But in the media industry, it’s a lack of education of the intersections of work, race and gender that leads to news outlets failing to call the shootings in Atlanta a hate crime in its first reports. Or, it’s the emotional labor Asian journalists are often expected to carry in newsrooms when reporting on events like Atlanta.

“It was heartbreaking to see again the media not know the kind of intersecting factors of racism and misogyny here,” Dr. Sharma said. “And so I think that also kind of allows us to understand or place this in the context of the history of sexualizing Asian and Asian American women.”

Dr. Barbara Kim, department chair of Asian and Asian American studies, explained that the Asian American history is one of exclusion, from immigration to becoming U.S. citizens.

The Page Act of 1875 prohibited immigrants from China, Japan or “any Oriental country” who were brought to the United States for work not of their free will or for “lewd and immoral purposes.” Importation of women for prositituon services was also prohibited, but as Dr. Sharma points out, it operates on the “basis that all Asian women are immoral or prostitutes.”

The Page Act was a discriminatory practice that singled out Asians coming to the U.S. and furthered the narrative that they were an undesirable class. Likewise, preventing Asian women from entering the U.S. separated wives from husbands and forced individuals to forego starting families in the U.S.

For the women who did try to come to the U.S., the experience was demanding.

Consuls of ports, as determined by the act, would make the determination if someone was entering the country freely and was not intending to enter and pursue “lewd” work. Asian women were subjected to multiple rounds of interrogations, being asked to answer their purpose for coming to the U.S., if they engaged in sex work, if they intend to live virtuous lives and so on.

Only seven years later, the Chinese Exclusion Act was signed into place, a law that limited Chinese immigrants from entering the U.S. and took away state and federal courts’ ability to grant citizenship to Chinese residents in the U.S.

Both these laws came about in the 1850s, when the U.S. began to see more Chinese workers come to the country, including working in California goldmines and working on railroads. They were blamed for taking work amid an economic depression in the 1870s.

In subsequent years, exclusionary acts continued to be passed, from the Scott Act in 1888, which eliminated the exempt statuses of Chinese laborers who should have been able to enter back into U.S., but were refused reentry. When the Chinese Exclusion Act hit the 10 year mark, the act was continued through the Geary Act and it wouldn’t be until decades later that these acts would be repealed.

During this time, the U.S. restricted the entry of another group of Asian immigrants. In 1907, the U.S. and Japan entered into a treaty known as the Gentleman’s Agreement, which regulated who could immigrate to the U.S.

It was determined that only educated Japanese persons could immigrate, not laborers, emphasizing long standing sentiments about how classism affects the treatment of immigrants.

In 1934, the Tydings-McDuffle Act imposed a limit of only 50 Pilipino immigrants a year to the U.S., a racist act disguised by the government who wanted to quell the increasing anti-Pilipino sentiments but could not outright exclude Pilipinos, seeing as the Philippines was a U.S. colony then. During this time, the U.S. was preparing to grant the Philippines independence, and therefore used that as a loophole to prevent immigration.

Though World War I certainly created anti-immigration sentiments, World War II erupted waves of hate and mistrust towards Japanese Americans, leading to an estimated 120,000 Japanese Americans being forcibly removed from their homes and places of work and into internment camps scattered in the U.S.

Families’ lives were destroyed, losing their businesses, their homes and limited to only being able to keep the belongings they could carry during the relocation process. Japanese Americans were forced to do manual labor, incarcerated for three years until the camps were ordered to close in 1945.

But, the internal actions are just one half of the country’s problematic history with the Asian community.

U.S. imperialism and colonialism in countries like the Philippines, Vietnam and South Korea have implications in our understandings of the present.

“The reality is the U.S. fought a lot of wars in Asia,” Dr. Kim said. “The U.S. occupied a lot of places whether it was the Philippines as an official colony or unofficially economically. So I think that there is a history of U.S. military, political, cultural, economic presence in Asia that is one of the reasons why a lot of us are here, and a lot of us have become now Americans in the process.”

Dr. Kim explains that economic systems surrounding military bases, such as sex work, meant that American soldiers would encounter Asian women in particular ways that affected perceptions of Asian women.

These perceptions linger today, arising in everyday encounters as journalist Jennifer Ho explains in her opinion article “To be an Asian woman in America.” Sometimes, Ho—and many others, for that matter—encounter white male veterans telling them war stories from Asian countries they fought in or that they remind them of women from there.

The Asian American relationship is ultimately a history of scapegoating, but it also raises another sentiment.

Dr. Sharma said that the salon worker community was one of the first places to reopen back in early May of 2020 without any time to prepare for a safe reopening operation.

“This has a lot of implications, again, on whose bodies are expendable, whose bodies are disposable,” Dr. Sharma said, explaining to think about this in a capacious understanding of violence. “So I think the choice that was posed here is reopen in order to go back to a low wage job and put your life at risk of the virus. And then given the kind of racialization and anti-Asian sentiment that was circulating, maybe put your life at risk of customers, which is what we saw here in the case of Atlanta.”

Asian immigrant women, Dr. Kim said, have “revolutionized” the beauty industry, but the cost is that immigrant owners and workers are being paid less. But the concentration of Asian immigrant women in the service work industry is a result of them being shut out from other industries, Dr. Sharma said, especially when certificates, degrees and cultural barriers prevented one’s work from being carried over into the U.S.

And in those spaces, where a service is being provided to someone, often engaging in direct contact like massages or nails, only further misconceptions.

But in a history built upon false narratives, there is still time to correct some, including one Dr. Kim points out. It is the statement that some have made in response to recent anti-Asian violence: We can no longer be silent.

“There have been many, many moments in Asian American history where people have not been silent and people have organized,” Dr. Kim said, explaining that Asian Americans haven’t been covering widely in mainstream media. “So there’s that invisibility and that feeling like all Asians…are doing really well, and they don’t experience discrimination. I think all of those things are being fought over because they are false narratives that make it very difficult for those in our communities who are experiencing this.”

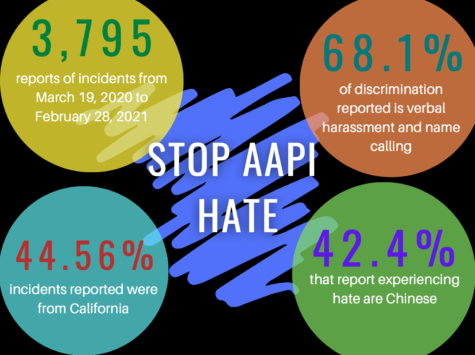

Visit Stop AAPI Hate’s website to learn more about the 2020-2021 national report, report a hate crime, learn how to stand with the Asian community and more. Visit Long Beach State’s Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies website to access a suggested reading list on anti-Asian racism and violence as well.

Editor’s Note: While Associated Press Style does not allow the usage of “Dr.” for a subject who isn’t a medical doctor, the editor is making an exemption to recognize the subjects in this story who do hold a doctorate degree.