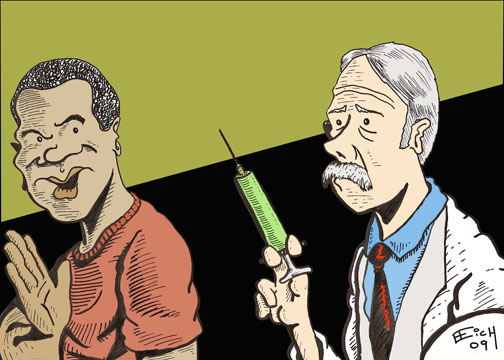

The horror stories and rumors traveling from mouth-to-mouth about H1N1 vaccine get more intensified each time they leave the lips of a new narrator. As much as we wish we were talking about a government scandal — or a California State University budget reform — the potential hazards of the vaccine are of greater concern.

Stories of children getting sicker or women becoming deformed after receiving a shot, are frightening people about how “unsafe” the vaccine to be.

Public health officials have noted five priority risk groups: pregnant women, healthcare employees, people aged 2 to 24, those aged 25 to 64 with chronic illnesses, Blacks and Latinos.

Although H1N1 can be life threatening to many in those priority groups, clinics in Los Angeles County find they are administering the vaccine to increasingly fewer minority groups, most notably blacks.

While blacks comprise 9 percent of the county’s population, only 2.57 percent of the initial 60,773 flu vaccines were administered to blacks; the minority group with the fewest number to have received the vaccine.

According to a Los Angeles Times/University of Southern California poll, an overall 17 percent thought the vaccine was unsafe, while twice as many blacks considered the vaccine too risky. The poll showed that some blacks have absolutely no plans to receive the vaccine.

Blacks are a priority risk group because they suffer disproportionately from illnesses like asthma, heart disease, diabetes and other chronic health issues. According to a study released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, blacks are four times more likely to be hospitalized for H1N1 than whites.

This is a critical reason that blacks should flood health clinics for the vaccine. When dealing with an illness like H1N1, ignorance will not be bliss and fear can cost lives.

Studies show that blacks are less likely to seek even a seasonal flu shot, have less access to public health care. Because of widespread myths and historical realities, many cannot be expected to automatically fall in love with the idea of a new type of flu shot.

Some officials, like L.A. County Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas, blame the low turnout on inadequate outreach by public officials to some communities. He said the government should not have anticipated a high turnout from blacks.

Others, like Loretta Jones, the chief executive of Healthy African American Families in South L.A., say many blacks either don’t know where the shot can be found or are skeptical about its safety.

Some have never forgotten the Tuskegee Syphilis experiment, when blacks were ill-informed by their government officials. The experiment was a 40-year study — between 1932 and 1972 — on the progression of syphilis if left untreated. During the span of the unethical study, 399 black men in late stages of syphilis were recruited.

The men were not told the severity of their illnesses and the researchers had no plans of curing them. This type of experimentation might be a reason why distrust of public health care is a common experience among many blacks.

In order to differentiate the benefits of the H1N1 vaccine from realistic fears of the Tuskegee experiment, public health officials are taking action by using the media to inform the public.

They plan to work with community groups like churches and schools, as well as respectable leaders in black communities, to help get the word out about the benefits of the vaccine — as compared to the ghost-like stories and rumors floating around about its negative repercussions.