Long before there were “Banana Pancakes” or you were humming the tune to “Upside Down,” the name Jack Johnson was synonymous with one thing: boxing.

One hundred years ago, he was the heavyweight champion of the world and the baddest dude around. However, there was a problem — Johnson was black.

In a time still filled with racial oppression Johnson’s color and even worse, his brash personality and blatant disregard for a manner in which he was supposed to conduct himself clashed with white authorities.

A century later, efforts are underway to right an egregious wrong.

A bi-partisan effort includes two bills, one in the House and another led by Republican Presidential Nominee John McCain is in the Senate. Both are awaiting approval.

In a letter to the President, McCain wrote, “Johnson’s conviction was motivated by nothing more than the color of his skin. As such, it injured not only Mr. Johnson but also our nation as a whole.”

If the bills go through, the dream of a posthumous presidential pardon for Johnson, a great American champion, could finally be realized.

While governor in Texas, George W. Bush tabbed Johnson’s birthday as Jack Johnson Day in the state for five consecutive years.

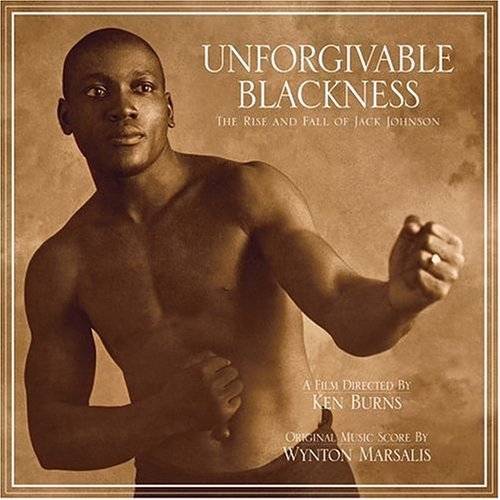

Legendary American filmmaker Ken Burns produced a documentary entitled “Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson” that aired on PBS back in January.

This movie has only furthered the effort to clear Johnson’s name.

Johnson was a larger-than-life American pop icon in the early 1900s.

Born in 1878 to former slaves in Galveston, Texas, Johnson’s meteoric rise and fall from failed Reconstruction America to heavyweight champion of the world does not have a happy-ending.

In 1913, Johnson was convicted of taking a woman across interstate lines as a violation of the Mann Act.

Officially the White Slave Traffic Act, the obscure and controversial measure was passed to combat prostitution at the turn of the 19th century.

The Progressive Era bill was being so broadly interpreted for anything other than spousal relations that any interstate travel, especially for “undesirables,” could mean prosecution.

After authorities were unsuccessful in nabbing Johnson on two occasions, they accused him a third time despite the consensual nature of his relationship.

These first two occasions, marriages to white women, sparked anger amongst a Jim Crow-era America.

Under law, once married, the women the authorities sought to testify against Johnson were no longer permitted to do so.

After sentencing, Johnson posted bail and fled overseas to Europe.

He tried to continue fighting while living in Paris but the marquee fights eluded him. The war was going on and Johnson was not the celebrity he was back in the states.

A convoluted title fight took place in Havana, Cuba in 1915 where Johnson lost a 26-round fight. Johnson’s loss meant the return of the title belt to a white man.

It would take 22 years for an African-American to have a chance to capture the title of heavyweight champion of the world again.

Johnson returned to the United States in 1920 and served his sentence. Once out of prison, he tried to resume his boxing career but he was never the same man, or the same fighter upon release.

He spent the rest of his days trying to live off his fading celebrity status. From exhibitions to entrepreneurship, he continued on.

Johnson was killed in an automobile accident in 1946.

Intelligent but flashy, charismatic and proud. Johnson was a victim of circumstance, torn-down by the times.

Amendments have been made to the Mann Act in recent years, most notably in 1978 and 1986, but the bill has never been repealed.

Notable stars like Black rock-n-roller Chuck Berry, actor Charlie Chaplin and architect Frank Lloyd Wright were all prosecuted under its auspicious umbrella.