Cal State Long Beach geological sciences assistant professor Nate Onderdonk received a $25,000 grant from the Southern California Earthquake Center to research the San Jacinto Fault, which goes through the middle of San Bernardino, about 75 miles northeast from Long Beach.

“The overall goal is just to get a better understanding of the earthquake hazard in Southern California,” Onderdonk said.

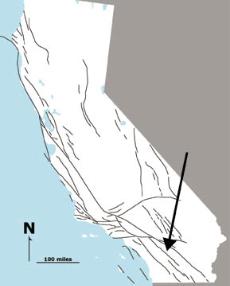

Onderdonk explained that there has been a lot of earthquake activity along the fault, which runs parallel to the San Andreas Fault.

“It has the highest number of small earthquakes of any fault in California,” Onderdonk said. “If you looked at the entire spectrum of small earthquakes, it’s probably like in the thousands, but most of them are so small that you don’t feel them.”

Onderdonk decided to do research on this specific fault because the San Jacinto Fault has not really gotten as much attention as some of the other faults in Southern California, such as the San Andreas Fault.

“Recent studies have come out showing that the southern part of the San Andreas may not be moving as fast as we thought, and the San Jacinto may actually be moving faster,” Onderdonk said. “So this might be a much more important fault than we had thought previously.

“One of the main reasons why I’m working on it is because there’s kind of a gap in our knowledge of Southern California faults right there. We don’t really know how it’s working and how it relates to the San Andreas.”

The grant will help Onderdonk fill in that gap. This is the second year Onderdonk has received a grant from the Southern California Earthquake Center, so the research will be a continuation for him.

The Southern California Earthquake Cent er is a community of more than 600 scientists, at more than 60 institutions worldwide, and is funded by the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Geological Survey.

The center helps develop an understanding of earthquakes and distributes data and information used to reduce earthquake risk.

“It’s a big deal for me because it provides the money to make it happen,” Onderdonk said. “For example, putting in trenches can be expensive because you pay to dig a trench. I can’t do it all myself. I need help from students, so the money to hire students is a huge help.”

Onderdonk will start the research this summer and will have two students who will help him – one graduate and one undergraduate.

Two goals they have in mind are to find when was the last major earthquake that actually broke the ground surface was, and how fast the fault is slipping.

“Basically we’re trying to figure out when was the last time there was a big stress release so we can estimate the probability of it happening in the near future,” Onderdonk said. “There’s the human aspect, that we want to be able to evaluate the earthquake hazard for societal value, but also for scientific value.”

Working with Onderdonk is geological sciences professor Thomas Rockwell from San Diego State University.

“We’re looking for sites that record a good sedimentation history, that buries an active major fault, and part of the reason we are doing this type of work is to try to understand how often earthquakes occur on different major fault segments, how large the earthquakes are,” Rockwell said.

Rockwell added, “We have very little information on that particular part of the fault in terms of its past earthquake history. We know it’s going to produce earthquakes. It can produce large earthquakes in the near future. We just don’t have enough information to accurately make a forecast.”

Onderdonk explained why he was so interested in earthquakes.

“I grew up in Southern California and I was always excited about earthquakes… I always wanted to know how the earth works, and what’s going on, so that kind of motivates me, just curiosity about the earth,” Onderdonk said.